A novel as circuitous as Darkfall by Dean Koontz, although awkwardly tawdry in terms of mechanics, is best understood as a fusebox of literary conventions. The afterword written by Koontz himself added to the end of the newest 2007 edition of this novel, which was originally published in 1984 , is telling:

I do not rate Darkfall among my best work, but I'll be immodest enough to say that I think it's a fun read. The only ambition here was to produce a page-turning entertainment; I wanted to cross the horror novel with the police procedural, while mixing a love story and a measure of comic dialogue.

Koontz is accurate when he describes his novel as a cross of the "horror novel with the police procedural." He makes no bones about his plot in

Darkfall being overly conventional and thus seemingly mechanical

. This is a fair description of the literary vision of Dean Koontz: always hinged on past conventions and stories.

But Koontz is a poetically crafty writer in

Darkfall. To make up for mechanical plots he hot-wires his reader

using po etically-loaded words into an underlying circuit board of familiar literary conventions. His words are electric in the sense that they spark "pure information" in the reader which can feel like literary

deja vu. Consider your reponse to the following passage:

"Look, Rebecca, I'm not saying it's voodoo or anything the least bit supernatural. I'm not a particularly superstitious man. My point is that these murders might be the work of someone who does believe in voodoo, that there is something ritualistic about them. The condition of the corpses certainly points in that direction. I didn't say voodoo works. I'm only suggesting that the killer might think it works, and his belief in voodoo might lead us to him and give us some of the evidence we need to convict him."

My response to this passage is literary: I see Koontz pointing to Harry Angel and the unconventional series of

bizarre and

occult investigations from William Hjortsberg's

Falling Angel. Reading this excerpt

I got the sense of

imitation or conventionality because the words and implied plot sounded like something fantastic out of a '50s pot-boile

r detective movie or novel. Only later did I associate these words, allegorically-speaking, with Hjortsberg's original 1978 noir detective thriller: "A spellbinding novel of murder, mystery, and the occult, Falling Angel pits a tough New York private eye against the most fearsome adversary a detective ever faced. For Harry Angel, a routine missing-persons case soon turns into a fiendish nightmare of voodoo and black magic, of dizzying peril and violent death -- a world in which the shadow he chases seems to be the shadow he casts."

This is why I enjoy Dean Koontz: his plots are mechanical, but his words electric.

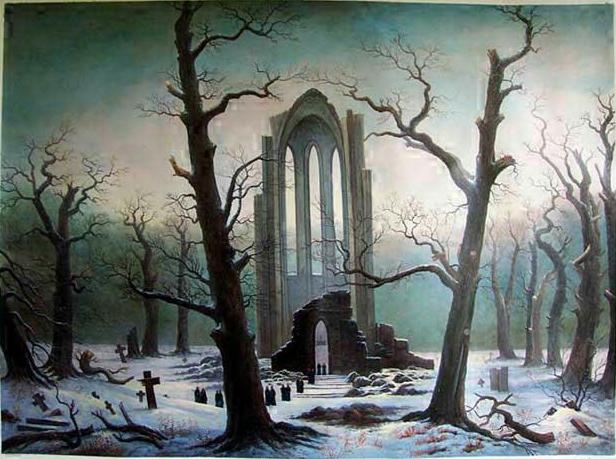

Nearly a week has passed, everything slow and languid, like all things in a heavy Canadian winter, including reading. As only a Canadian ought to in winter, I have just finished reading the Governor General's Award and Scotiabank Giller Prize nominated novel The Immaculate Conception by Gaétan Soucy, translated into English by Lazer Lederhendler. To everything there is a season, and especially when it comes to reading Canadian Literature, that spirit of pathetic fallacy borne in the Canadian-born reader seems to have an affinity for winter, inwardly. Reading Todd Swift's dark and stormy description of Soucy's novel from his article "Monsters as People" in the January/February 2007 issue of Books in Canada: The Canadian Review of Books opened a window to the possibility of Great Can Lit for me:

Nearly a week has passed, everything slow and languid, like all things in a heavy Canadian winter, including reading. As only a Canadian ought to in winter, I have just finished reading the Governor General's Award and Scotiabank Giller Prize nominated novel The Immaculate Conception by Gaétan Soucy, translated into English by Lazer Lederhendler. To everything there is a season, and especially when it comes to reading Canadian Literature, that spirit of pathetic fallacy borne in the Canadian-born reader seems to have an affinity for winter, inwardly. Reading Todd Swift's dark and stormy description of Soucy's novel from his article "Monsters as People" in the January/February 2007 issue of Books in Canada: The Canadian Review of Books opened a window to the possibility of Great Can Lit for me: